Mobile-izing Savings with Defaults in Afghanistan

Perhaps the most cited triumph of behavioral economics – that marriage of economics and psychology that has put terms such as “nudge” and “fast versus slow thinking” into the popular lexicon – is the automatic opt-in. For example, more people donate organs if they are automatically put on the organ donor list. And far more people contribute to retirement accounts when they are automatically enrolled by their employer. The power of the default option is part of why 401(k) plans are so popular in the United States. Savings programs that automatically enroll people by default, or that define a default savings amount, generally seem to help people save. By contrast, when employees must make an active decision to opt in, overall rates of savings are much lower.

Along with other aspects of financial inclusion – ubiquitous ATMs, reliable and accessible financial information – default savings programs seem to be the province of rich countries. But recently, the world has seen a dramatic drop in the numbers of unbanked citizens due to the spread of mobile banking, particularly in East Africa. The number of people with phones is far higher than the number of people who have easy access to traditional bank branches, especially among the rural poor. Until now, however, no one (to our knowledge) has tested whether mobile banking can facilitate default savings programs.

This is exactly what our team set out to do in Afghanistan. For the past few years, we have been testing financial inclusion products with Roshan, the country’s leading mobile communications provider (and largest taxpayer). Our recent investigations have focused primarily on the power of the default and the automatic opt-in. We were interested in understanding whether such innovations could work in a developing-country context, and also exploring whether low levels of savings is due to forces we see in the West (such as aversion to complex decisions and a tendency to procrastinate) or those particular to poor and unstable countries (distrust of banks among citizens, low amounts of cash on hand).

If you’re going to study the determinants of extremely low financial inclusion, Afghanistan is a good place to start. According to the World Bank’s 2014 Global Findex Report, only 10 percent of Afghans have a bank account – that puts them in the sixth-to-last position of over 140 countries covered by the report. Compare that to 46 percent for the South Asian region as a whole. Only 4 percent of Afghans have savings accounts versus 13 percent for the region and 52 percent for the OECD (a club of developed countries).

But 60 percent of Afghans have mobile phones.

Our sample population was Roshan’s entire 1,000-person workforce – from janitors to executives – all of whom had easy access to a mobile phone. We should point out that with monthly salaries ranging from $50 to $3,000, this population is not representative of the truly poor, and as employees of a prominent company, they are not representative of the huge informal workforce in Afghanistan and other poor countries. [1]

In collaboration with Roshan, we designed and implemented a savings product that could automatically deduct savings from employees’ salaries. This product, called M-Pasandaz (“M-savings” in Dari), added a second wallet to the mobile money interface, to store the portion of an employee’s salary that had been automatically deducted from their monthly salary. Employees could elect to have anywhere between 0 percent to 10 percent of their salary automatically deducted each month. Changing this allocation only required that a short call be made to the human resources department at Roshan. To test the importance of the default effect, half of all employees were randomly selected for automatic enrollment at a 5 percent contribution rate. The remaining half was initially “opted out” at a 0 percent contribution rate.

We found that employees who were automatically enrolled to have 5 percent of their monthly salary deducted were 40 percentage points more likely to contribute to the savings account than those who were not.

To explore this finding in greater detail, we further randomized those within the savings group into a matching incentive treatment. Here, employees received one of three plans: the Red Plan, where their employer matched their contributions to their savings accounts at a rate of 50 percent up to 10 percent of their salary (meaning if you saved a dollar, your employer contributed 50 cents to your savings account); the Blue Plan, where the employer gave a 25 percent match for contributions up to 10 percent of salary; and the White Plan, where employees got no match on the money they put into savings. In the White Plan, there was no penalty for withdrawals, but in the other two, if you withdrew money within six months you forfeited all the matching funds you had earned.

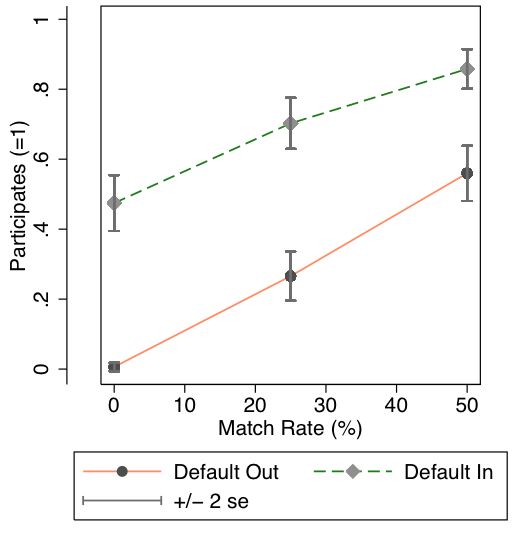

Among those who were randomly defaulted out of automatic contributions, and relative to a baseline of no matching incentives, we found that the Red Plan (50 percent matching) increased employee participation by 47 percentage points, and the Blue Plan (25 percent match) by 25 percentage points. This graph summarizes the results.

What this boils down to is proof of the power of the automatic opt-in: The effect of automatic enrollment on participation is about the same as providing expensive financial incentives (a 50 percent match on the part of the employer).

The effect of both the automatic default and the incentive match was substantial. Across all of the employees (including those who did not contribute anything over the course of the pilot), we find that after six months employees had accrued an average of about 5,900 Afghanis (92 dollars) in their account – or about a week’s salary. Those who did contribute accrued an average balance of about 12,600 Afghanis (200 dollars) – or about two weeks’ salary. (Neither amount includes the match provided by Roshan.) Through surveys with employees, we see that this is largely new savings, rather than simply a reallocation of the financial portfolio. For instance, in the final month of the program, we find that employees receiving the 50 percent match had twice the total monthly savings of employees receiving a 0 percent match.

In the end, the program proved very popular with employees – over 45 percent chose to continue with monthly contributions even after matching incentives were removed at the end of the study. Meanwhile, Roshan is actively considering providing a 50 percent match for up to 10 percent of employees’ salaries for automatically deducted contributions.

The program successfully increased savings, but why does default enrollment increase participation so effectively? One possible answer is that people simply didn’t pay attention, and stayed in the program out of mere inertia. We were able to rule this out using data gathered from surveys, and by sending randomly selected employees different types of text and phone reminders that drew attention to the savings plan.

Other possibilities are that default enrollment overcomes people’s propensity to procrastinate, or it sidesteps having to deal with complex financial issues. (It takes a real interest in finance – or a particular type of masochism – to want to read detailed financial forms.)

To explore these possibilities, we randomly offered employees a free telephone financial consultation designed to take the pain out of selecting a contribution rate. We randomly offered to provide some employees the consultation the same day we contacted them, and offered to provide it to others the week after. While 70 percent took the offer for the same day, 76 percent took it for the next week. Restricting our sample to those that we identified as “present-biased” using a laboratory exercise, we found that the gap between those taking the offer on the same day and those taking it next week grows to over 13 percentage points. This suggests that defaults raise contributions because people perceive financial decisions as complex and if they were left to themselves, they would procrastinate in developing a financial plan and making contributions.

So, broadly speaking, employees in a country plagued by poverty and insecurity show the same behavioral biases as employees in rich countries. We hate filling out forms, and we’d rather put off complex decisions and boring conversations. These tendencies can hurt us financially in the long run.

Across the developing world the population in extreme poverty is shrinking, and the middle class, expanding – and with it the number of wage workers. Our results suggest that, as mobile coverage expands and technology gets cheaper, there is increased scope for using automatic enrollment to nudge more people into investing in their own future stability.

Editor's note: this is a cross-posting with NextBillion

Note: This study was supported by the Citi IPA Financial Capability Research Fund, a fund within IPA’s Financial Inclusion Program which supports research on innovative products and programs that aim to improve the financial capability of low-income people in developing countries.

Photo credits: Jan Chipchase.

[1] Blumenstock, Joshua, Michael Callen, and Tarek Ghani (2015) “Mobile-izing Savings with Automatic Contributions: Experimental Evidence on Dynamic Inconsistency and the Default Effect in Afghanistan,” working paper.