Introducing IPA’s Strategic Ambition 2025

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series on what IPA has learned about making sure evidence gets used, and what we, as an organization, hope to do more of in the future. Part two, on how to co-create evidence with partners to make sure your questions are relevant to them is here, and part three on what to do after you've done the research to make sure it gets used is here.

On the plane to the Ghana Education Evidence Summit 2017—the first time IPA and the Ministry of Education co-hosted a large education conference showcasing our partnership there—I found myself reflecting on our work in education in Ghana so far. It was clear to me that, in part through the co-leadership of IPA, the Ministry of Education, Ghana Education Service (GES), and researchers, the culture of decision-making in Ghana’s education sector was changing. To that point, we had collaborated on eight evaluations. The evidence on targeted instruction was evolving into the first at-scale randomized evaluation of targeted instruction on the continent; IPA and our partners seemed equally invested in finding a way to effectively scale that proven intervention. In addition, the Ministry and GES partners were increasingly coming to IPA with complex evidence questions around how they could create more of their own rigorous evidence and collect more high-quality data around the policy decisions they faced.

It was clear we were making progress (and clear that there was more progress to be made) but while I reflected on it, I was struck by a tension that has emerged many times in my experience in the sector: why do some policy and research collaborations move forward to impact policies and programs, and others don’t? While I’m happy about our successes, I also sometimes feel uneasy—wondering why this one and several others have caught on, while other incredible research remains on a shelf. I wondered: How had this come to be? Why Ghana? Why education? And—why IPA?

What does it take to move evidence to policy?

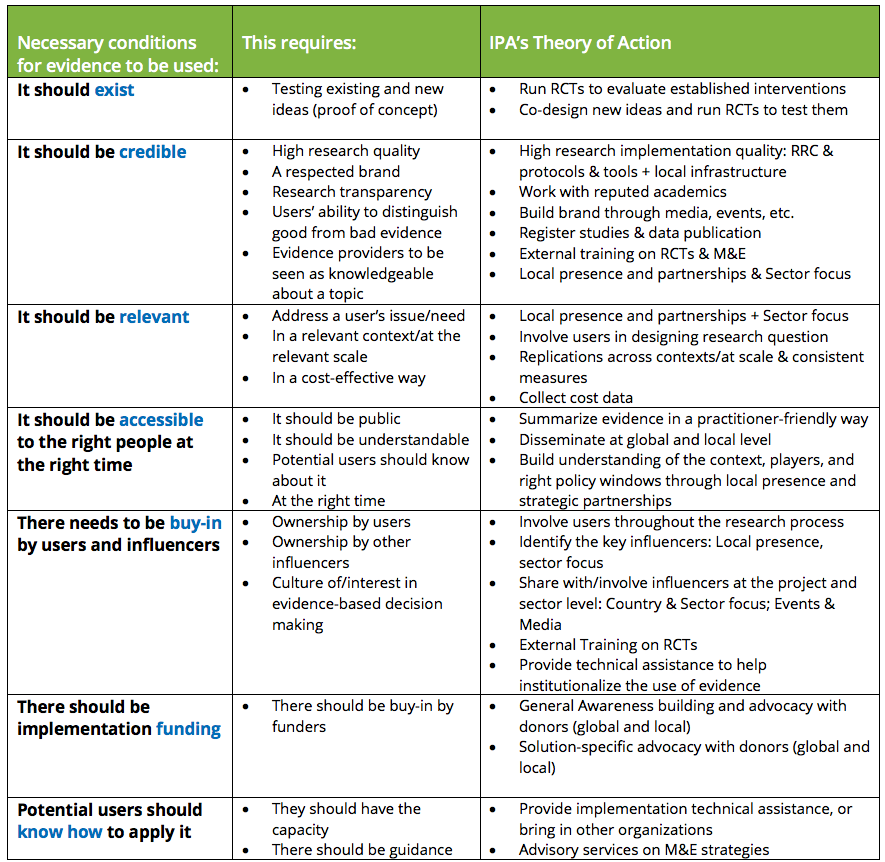

IPA has had a theory of change for 15 years, but on that plane ride, I drafted IPA's Theory of Action, drawing on our experiences and that of our partners: the conditions necessary for evidence to influence policy, and the work IPA does to create those conditions. I’ve seen this in action throughout our 21 country offices and 8 sector programs.

Necessary conditions for evidence to be used (see below for the full Theory of Action):

It should EXIST

It should be CREDIBLE

It should be RELEVANT

It should be ACCESSIBLE, to the right people AT THE RIGHT TIME

There needs to be BUY-IN by users and influencers

There should be implementation FUNDING

Potential users should KNOW HOW to apply it

Listing them out makes me think no wonder plenty of good findings languish in the purgatory of working papers and briefs! But also it illustrates why some findings do actually get used – and most importantly how to ensure they do. Thinking about our work this way kicked off a year-long process through which IPA thought about what we need to do to change this, and galvanized us to think about what a research organization needs to do beyond research if they really care about change. The result is a map for our path forward from 2018 through 2025. We’ve just released the public version here.

From “discover and promote” to “create, share, and equip”

Perhaps the biggest shift reflected in our 2025 Strategic Ambition is our realization that “promoting effective solutions”—a key phrase in our current mission statement—is not enough for evidence to systematically inform decisions. Because of this, we are intentionally growing our ability to equip decision-makers to use evidence. This means helping them create better data and leverage it, create and understand their own rigorous evidence, and working to establish a culture of evidence-informed decision-making within organizations. We are also aiming to increasingly embody what it means to build learning organizations: supporting ongoing learning—for ourselves and for our partners—about why certain interventions work, under what circumstances, at what scale, through which delivery mechanisms, etc. To quote from the Ambition:

“Our strategic ambition through 2025 emphasizes the need for iterative learning about what works (and doesn’t work!), and why, and the need to equip decision-makers to use evidence, by building deep partnerships, engaging decision-makers throughout the research process, and helping them develop learning agendas adapted to their needs.”

This change means that IPA is now thinking about our work in terms of three pillars:

What isn't changing:

I would be remiss not to emphasize that there are some things that will not change, particularly in our first pillar: IPA continues to be known for and founded on the rigor and high quality of our research, conducted in collaboration with over 500 of the brightest minds in our field. This won’t change – we plan to only strengthen and deepen this work by pushing the limits of research innovations, studying promising programs in other contexts, and continually improving our (and our partners) data quality.

Introspection and reflections from throughout the sector

Finally, as I look back on the many months of reflection and analysis that went into this process, I am as grateful for the journey as I am for the result. One of the most special aspects was that dozens of our partners lent us their insights through semi-structured interviews. This process was incredibly helpful and reminded me how lucky we are to be surrounded by brilliant partners who care so much about IPA’s work. A few of our most insightful partner quotes:

- “I would like IPA to continue to be the liaison between government and researchers to help them answer key questions. For [our study], IPA helped redirect us to do something scalable, sustainable, and that was not the initial direction. This knowledge about key government questions is not something we can do as researchers sitting in another country. That expertise and partnership is so valuable.” Sharon Wolf, Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania

- “IPA played an important role in lending credibility and helping disseminate study results to people that make policy decisions in our sector... They also have deep graduation sector expertise which has been helpful in bringing others to the table and encouraging unbiased policy decisions." Dianne Calvi, CEO of Village Enterprise

- “[Our Ministry] officers are currently handicapped in conducting research that can be presented in big fora and research that can have an impact. The question we should be asking ourselves is: how can partners like IPA help the planning unit move from the current desk work and firefighting scenario to looking at figures to inform and advise the senior officials, forecasting trends and planning from the district to the national level?” (Government partner)

Internally, we also brainstormed what we imagined the best and worst potential headlines for IPA might be in 2025, which ranged from the idealistic to the frankly frightening:

Best potential headlines for IPA in 2025 | Worst potential headlines for IPA in 2025 |

“IPA research changes development practice around the world” “Rigorous use of data and evidence now standard practice for all development investments over $1m” “IPA is go-to shop for development funders and implementers who want to invest in what works” | “Millions of dollars spent on poverty research: Where is the impact? “All research done by prestigious NGO found to be built on methodological house of cards” “IPA buried research on XXX because funder ZZZ asked them to keep quiet: Thousands of program participants affected” |

Most of our internal work was done through working groups, who focused on our three pillars. We had lively debates over how introducing the Right-Fit Evidence Unit will enhance IPA’s partnerships; where the next frontiers of poverty research are opening up; and whether we are delivering on our current mission and where we need to grow. In several blog posts over the next few months, IPA colleagues will share more about these reflections and debates, so do stay tuned for more on what we have learned.

I’m excited about what the next several years hold for IPA and our partners. I hope you will join us in this ambition, as we continue to build a world with stronger evidence and less poverty.