After a decade of partnership and over half a dozen co-created rigorous evaluations, in the summer of 2019 the then-Minister of Education of Ghana described what he saw as the next step in the collaboration between IPA and the Ministry: “You need to embed yourselves.”

Building on a model that IPA and partners piloted and built within the Ministry of Education in Peru (MineduLAB, an innovation lab that now runs autonomously within the office of monitoring and evaluation at Minedu), IPA took on the Minister of Education’s challenge and began to adapt the embedded lab model to meet the opportunities in Ghana’s public education system. This brief shares that process, the lessons learned, and takes a look ahead at what is next for Ghana’s Embedded Evidence Lab.

|

What is an embedded evidence lab? Embedded Labs are teams of IPA and public sector colleagues working side-by-side to strengthen the use of data and evidence in public policy. Each lab works on a variety of activities to equip IPA’s partners to regularly use evidence to improve their decision-making, policies, and programs. Think of labs as IPA for the government. |

The Origins of a Learning Partnership

IPA has established a longstanding relationship with Ghana’s Ministry of Education (MoE) that dates back to 2008. IPA first partnered with Ghana’s MoE to measure the short- and long-term impacts of providing full, needs-based scholarships to secondary school students through the Ghana Secondary Education Program. Since 2008, IPA Ghana and the MoE have collaborated on seven studies, reaching almost 70,000 learners.

The relationship between IPA and the Ministry of Education in Ghana has progressed into the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with both GES in 2017 and the MoE in 2019. The MoUs formalized our existing partnership in developing rigorous evaluations of proposed education programs, providing credible empirical evidence from research programs to inform policy decisions, and collaborating on the capacity-building of staff in research and evaluation processes.

Embeddedness & Adapting the Lab Model to Ghana

As part of our partnership, IPA has a staff member embedded in the MoE to support evidence-driven policy capability from within the ministry. This embedded staff member is supported by various research, policy, and Right-Fit Evidence staff within IPA to provide the MoE with the full range of IPA’s capabilities and expertise—and begin the transfer of that expertise to the Ministry. Although the initial approach (modeled on IPA’s experience in Peru) was to provide technical support from a central location within the Ministry, it became important to structure our support to fit the way the Ministry’s work is structured: along the lines of priority programs of its various agencies and sub-groups.

|

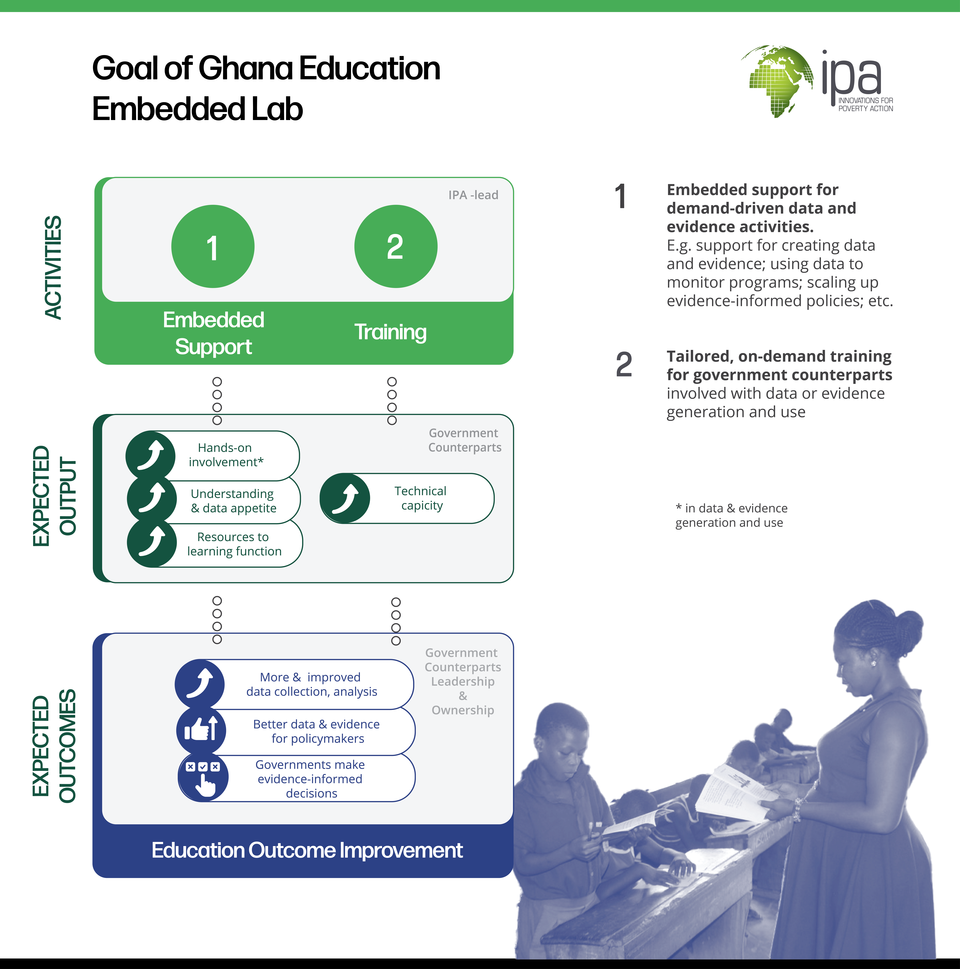

How can embedded evidence capacity improve learning outcomes? (i.e. what is the theory of change for reaching meaningful impact? The goal of the embedded lab is to equip the Ministry of Education to make evidence-informed decisions that improve learning outcomes. Our approach is to 1) improve the data and research capabilities of Ministry agencies and 2) institutionalize the use of data and evidence to inform decision-making. The ultimate goal is to improve education outcomes.

|

Partners and Achievements

1. Ghana Education Service: Evidence-Informed Differentiated Learning for Improved Outcomes & Impact at Scale

In 2013, IPA partnered with Ghana's Ministry of Education to implement the first evaluation in Africa of differentiated learning (DL). This evaluation found significant improvements in numeracy and literacy on average, with regional variations highlighting the importance of implementation quality.

Building on this research, a second study, Strengthening Teacher Accountability to Reach All Students (STARS), implemented by the MoE and Ghana Education Service (GES) with technical assistance from IPA, and technical and financial assistance from UNICEF, directly focused on the issue of implementation fidelity and evaluated an improved version of DL with extra focus on management and program compliance. This version improved math and English learning for students in Ghana, while also improving implementation of the program. Student achievement gains in the one-year STARS program were larger than those estimated for the students in the earlier program who experienced teacher-led differentiated learning for two years.

In response to this research, Ghana's MoE has incorporated DL based on the STARS model into the Ghana Accountability for Learning Outcomes Project (GALOP), a US$219 million fund from the World Bank and Global Partnership for Education. The fund will pay for the implementation and scale-up of effective education solutions in 10,000 of the lowest-performing schools in Ghana, reaching over two million learners—a win for evidence-informed policymaking in Ghana and the education sector.

IPA, via the embedded lab and in partnership with UNICEF and others, will support GES as they train teachers in new schools on DL instruction and bring this evidence-informed program to scale.

2. National Council for Curriculum and Assessment: Rolling Out a New Curriculum with Data-Driven Decision-Making

In 2019, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NaCCA) within the MoE rolled out a new basic curriculum for students from Kindergarten to Primary 6 across Ghana. IPA supported NaCCA to develop evaluation tools and collect data, analyze it, and generate reports for the training for the national basic curriculum rollout. These tools allow NaCCA to ensure that teachers are well-prepared to use the new curriculum by identifying and addressing any gaps in teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Ultimately, this will lead to improved standards of teaching and learning outcomes for students in Ghana.

IPA guided NaCCA to identify measurable indicators and develop monitoring tools that guide the improvement of the training at the national and master trainer levels. Through this process, NaCCA saw the value in the process of monitoring—how it enabled them to identify and fill gaps in the training they were doing on their new curriculum, and roll out the new curriculum in a more data-driven process. This led them to invest their own resources in creating their own M&E team. NaCCA’s M&E team then trained GES officials to adapt the M&E process at the regional and district levels.

The M&E team at NaCCA expressed interest in receiving support from IPA to apply the lessons learned to inform M&E planning for the junior and senior high school curricula. In 2020 and 2021, IPA supported NaCCA with designing tools for the evaluation of the training for the junior high school curriculum roll-out. This time around, IPA has been able to be much more hands-off, as NaCCA has led more of the process, directing more of their learning.

3. National Kindergarten Policy: Equipping the Sector with Evidence

Results from several IPA early childhood education (ECE) evaluations including the Fast Track Transformational Teacher Training (FTTT) program, Quality Preschool for Ghana (QP4G), and Lively Minds have been key in informing the Ghana Ministry of Education’s national ECE policy, through IPA’s involvement in shaping the latest policy. IPA research findings have informed the parts of the policy aimed at strengthening pre-service and in-service teacher education and training, play-based learning, and parental engagement.

Through a coalition with UNICEF, Sabre Education, Lively Minds, GES, and many others, built to ensure that the national ECE policy is informed by evidence, evidence-informed programming will reach over 61,000 kindergarten teachers and 1.8m children across more than 25,000 schools.

4. National Inspectorate Board: Digitizing Data Collection for Identifying Schools in Need

High-quality school inspections help Ministries of Education systematically identify schools in need of greater attention. Prior to IPA’s involvement, NIB was conducting all school inspections using paper tools and did not have a rigorous system for sampling schools to inspect (potentially oversampling schools that were easy to reach or inspect for other reasons). To alleviate these challenges, IPA worked with NIB to support the design and piloting of the KoBoCollect (digital) classroom inspection tool and give advice on managing, validating, analyzing, and visualizing data from the tool. IPA also supported the drafting of a data management and analysis plan that outlined staffing requirements to ensure the smooth running of the data management system.

Based on this experience, NIB saw the value in a rigorous sampling system as well as a more robust data collection and analysis process. They hired a data analyst to manage the inspection data and trained their IT technician to program the inspection tools on KoBoToolbox. NIB was successfully able to implement the first round of their inspection exercise and come up with an analysis of the results. In 2021, NIB was able to draft a KG inspection tool with minimal support from IPA.

5. Education Sector Research Group

The Education Sector Research Group (ESRG) provides a platform to prioritize and conduct research for pressing education challenges and facilitates the MoE’s efforts to ensure its policies and programs are informed by evidence. The ESRG is expected to deepen and expand mutual learning between decision-makers and researchers in the education sector, and aims to increase engagement with local researchers who are interested in ensuring their education research is policy-relevant.

IPA is working with the MoE to set up and facilitate the ESRG, strengthening the MoE’s capacity to connect policymakers and researchers and ensure the utilization of evidence generated through ESRG activities. IPA has supported the MoE to convene several ESRG meetings over the past year that have focused on sharing survey results on the impact of COVID-19 on the education sector and developing objectives for prioritized research questions. The MoE has now invited ESRG members, including IPA, to submit proposals to undertake research on some of the prioritized research topics.

This is a strategic activity for the lab as it serves to both enhance research and evidence capacity at the ministry, while also increasing the ministry’s ownership of these activities. While the ESRG convenes Ghana’s education sector to create consensus around a research agenda, the lab unlocks education data that can be used widely to pursue projects on that co-created research agenda. We expect that this will result in evidence-informed education policy decisions and improved service delivery within Ghana’s education sector.

Looking Ahead

The embedded lab workstreams are ongoing, and IPA and the MoE continue to partner together with others in the education ecosystem to scale evidence-informed interventions—such as differentiated instruction and play-based learning—to reach millions of learners in Ghana. Through these experiences and others, the lab will continue to institutionalize the process of data and evidence generation and use, continuing to transfer ownership and responsibility for these activities to the ministry.

Ownership Transfer and Exit Strategy

IPA’s model for support has been focused on sustainability: building systems that will outlast our direct support. For individual workstreams, this has looked like progressive phase-out of our direct involvement, in approximately the following process: (a) doing M&E activities side-by-side with the agency; (b) the agency seeing the value of the activities, and hiring/designating its own staff for these activities; (c) these agency staff doing the activities with our support (this time the agency is in the "driver's seat", while IPA is observing and guiding); (d) the agency becoming confident to do these activities, with their systems having developed for the smooth running of the activities. This work has enabled us to see the ways in which our long-term partnership and ongoing collaboration has encouraged the Ministry of Education to begin making its own investments in rigorous data- and evidence-informed policy.

This exit strategy has been successful with NIB and NaCCA as detailed above, and we are aiming to facilitate a similar process with other agencies, the MoE, and GES, especially as GALOP-led DL and ECE work is rolled out and scaled. As we do with MineduLAB, in the long run, we will remain available as a partner for technical assistance, design and implementation of rigorous and complex evaluations, and other roles that the public education sector won’t take on itself.

|

What’s been learned?

|