Tracking the Real Cost of Mobile Transactions: IPA's New Two-Year Pilot

Ask a taxi driver in Kampala if you can pay your fare with mobile money and you’ll likely be told: yes—but only if you cover the fee to withdraw the money to cash. Despite the benefits of mobile money, many still choose to use cash, at least in part because of the high cost of mobile money transactions. Economics 101 tells us price and demand are closely linked, and evidence suggests this relationship is particularly strong for mobile money. For example, when Rwandan telcos made transactions free in early 2020, mobile money transfers ballooned to five times their pre-pandemic levels.1 Mobile money has the potential to be a poverty-alleviating tool that can change trajectories of lives2; yet researchers and policymakers don’t have a systematic way to know what consumers pay for mobile money transactions, a key factor affecting take-up and usage. IPA seeks to fill this gap by developing and testing cost-effective means of measuring the cost consumers actually pay for mobile money transactions across a set of low-and middle-income countries.

Every day, more than $2 billion is processed globally by mobile money operators3 as users store, transfer, and spend money with their phones. Even a low-tech phone (or one shared by a group of people with their own SIM cards) can let people participate in the financial system without ever stepping foot in a brick-and-mortar bank, making it a particularly useful tool for poor and rural populations. Over the past decade and a half, mobile money has provided millions with access to formal financial products and brought about a range of rigorously demonstrated benefits to consumers. For example, mobile money lets family members who've moved to the city send money back home instantly and reliably, instead of handing it to a bus driver and hoping it gets there; it allows households facing an emergency like a lost job or unexpected hospital visit to collect monetary support from friends and family, no matter where they live.

Despite the benefits of mobile money and its growing availability in low-and middle-income countries, access and usage remain persistently low in some poor communities and the cost of mobile money is almost certainly a contributing factor. Costs can be high, particularly for low-value transactions where fees exceeding 10 percent of the transaction value are not uncommon. Researchers can use data on transaction costs to understand what influences them and how consumers respond to changes. For example, in related work, IPA is investigating whether financial providers’ backend systems being able to communicate with each other leads to customers paying less to send money.

Costs can be high, particularly for low-value transactions where fees exceeding 10 percent of the transaction value are not uncommon.

Transaction prices are often regulated, but these rules are not always followed. Governments can use this new data to monitor compliance with regulations, see how their transaction costs stack up with costs in peer countries, and even incorporate these costs into macroeconomic planning tools (for example, as a component of consumer price indices). Financial service providers themselves can monitor compliance with their own rules and ensure their prices remain competitive in the market.

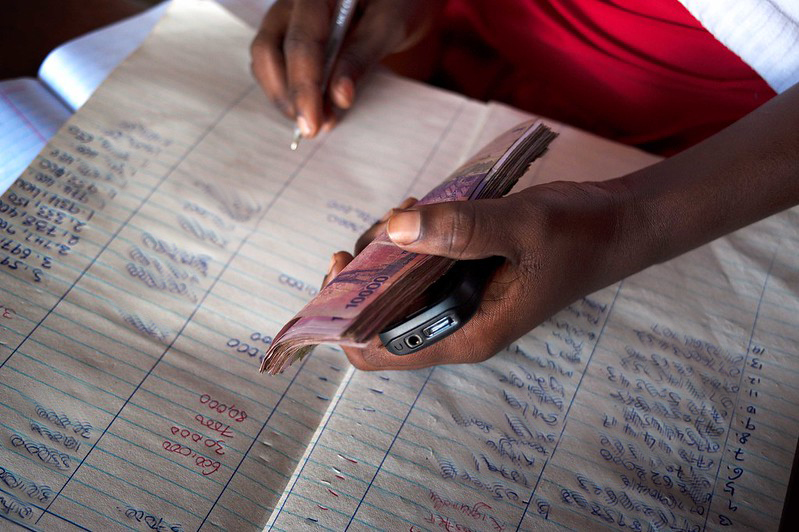

But wait, you might be thinking, mobile money fees are just a Google search away. Could I run this study from my couch? Unfortunately, no (though we support couch research—desk research is so 2019). Official fees don’t always reflect what consumers truly pay as overcharging by agents is commonplace in many markets.4 Additionally, the true cost to make a transaction includes more than the fee itself. Non-monetary costs can be significant, for example, time customers spend waiting to complete a transaction or being unable to access their money because of network outages or agents lacking cash or float.

With funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, IPA’s Financial Inclusion program will develop a transaction cost index (TCI) to track the real costs of using mobile money for deposits, transfers, and withdrawals. In Bangladesh, Tanzania, and Uganda, we’ll start with “mystery shopping” audits, where trained shoppers replicate typical customer interactions at places of business and record exactly what happened. In our case, mystery shoppers will visit mobile money agents, attempt transactions such as depositing money into their account, and record the official and unofficial fees charged by the agent along with the quality of agent services, and any related conduct issues.

While mystery shopping is considered the most accurate way to collect information about how businesses operate, executing an audit is complicated and expensive. To determine the feasibility of scaling the index in the future, the project will also explore if we can capture costs using three less expensive methods: 1) intercepting customers at points of surveys and asking them about their experience; 2) deploying mystery shoppers remotely by transferring money to local consumers and asking them to conduct and record transactions, which would likely be cheaper than using professional shoppers; and 3) crowdsourcing costs directly from consumers via a mobile application. This effort will be led by Xavier Giné of the World Bank who pioneered the use of mystery shopping for financial services in emerging markets and Francis Annan of Georgia State University, who studies digital financial products, including (mis)behavior of mobile money agents in Ghana.

Our focus now is on developing an accurate, cost-effective approach to measuring transaction costs that can work across many contexts. We hope that once we’ve developed a cost-effective tool, it can be implemented in a broader set of countries on a continual basis, similar in scope to work by the World Bank measuring cross-border remittance prices. It makes a big difference whether it's a 500-shilling fee to withdraw your money on paper or it’s really in practice 500 shillings to the bank, 500 shillings to the agent, and a long wait to get your funds. Tracking the actual—not just theoretical—cost to users over time and across multiple markets would expand the possibilities for researchers and practitioners focused on improving the quality of, and access to, financial services for the poor.

- See this Economist article. Of course, a lot else was happening in early 2020 so it’s hard to be sure what caused what.

- For a comprehensive summary of mobile money’s benefits, see this VoxDevLit review.

- See this Groupe Speciale Mobile Association (GSMA) report.

- See for example IPA’s Consumer Protection in Digital Finance Surveys which found more than 30% of digital finance consumers report agent overcharging in Uganda and Nigeria.