The Socioemotional Toll of COVID-19 on Families in Peru

By Juan M. Hernández-Agramonte (IPA), Claudia Paola Lisboa Vásquez (OSEE, Minedu), Carolina Méndez (IDB), Olga Namen (IPA), Emma Näslund-Hadley (IDB), and Luciana Velarde (OSEE, Minedu)

Editor's note: This is a cross-post of a blog that originally appeared on IDB's blog page (in Spanish).

Following school and workplace closures and layoffs throughout the world, mental health experts caution that lengthy shelter-in-place orders may have severe effects on our socioemotional wellbeing. With all of us separated from friends, everyday interactions, routines, and structures, struggles with loneliness, anxiety and depression are rising.

For children and teens around the world, extended lockdowns and school closures can be particularly traumatic. In many children and teens, the separation from friends and everyday routines is causing anxiety, grief, anger, and loneliness. These children and teens may be dealing with the loss of a parent or grandparent or have parents who have lost their livelihood, in addition to their own fears about the virus. Other stressors may exist in their households too—domestic violence and substance abuse have increased since the pandemic began. Mental health consequences on an unprecedented scale among children and adolescents are looming.

Although the full effects of the lockdown on children’s mental health will only be fully apparent in the longer term, it is already possible to see how the pandemic is impacting different groups of children differently. In Peru, the Ministry of Education (Minedu), with the support of IPA and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), asked 8,000 families about the socio-emotional health of children, adolescents, and caregivers.1 This information gives us a first window into how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the health of children and youth, an essential first step in designing education and health policy responses.

Social distancing is particularly hard for teenagers.

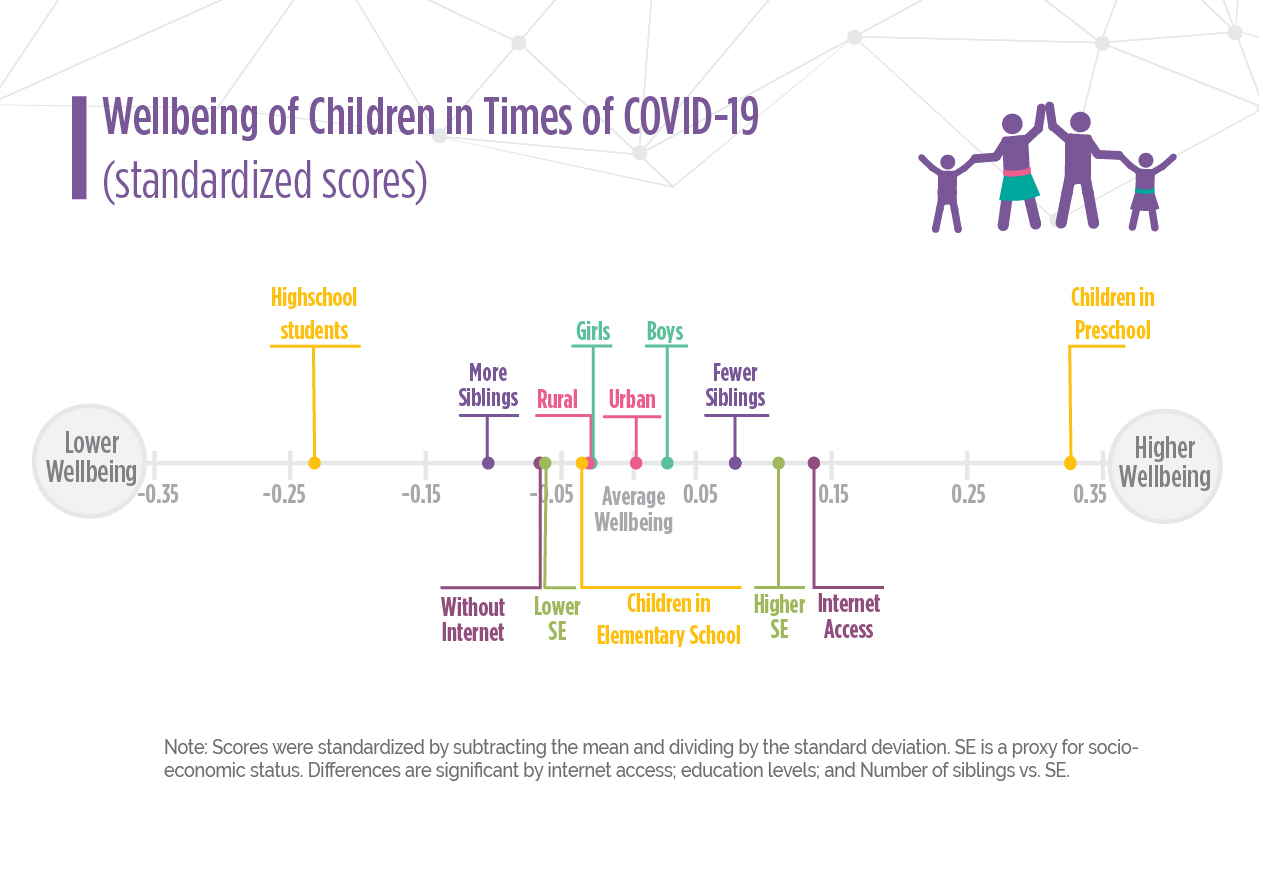

We find that on a mental health index, teens scored eight percentage points lower than elementary school-age students. There are many possible reasons for this. On one hand, teens are wired to separate themselves from their parents as their brains and bodies prepare them for independence, which makes sheltering-in-place with parents more challenging. It is also likely that teens are taking on multiple new responsibilities during lockdown. This would be consistent with recent findings from Ecuador, which show that teenagers are spending time on household tasks and work in addition to their schoolwork. In particular, teens with lower household wealth have less leisure time than their peers in wealthier families.

Teenage girls in our sample have lower reported wellbeing than teen boys. This may result from teenage girls taking on more household responsibilities. Although we did not include this question in our survey, during the pandemic in Ecuador, teenage girls engage in less leisure activities and more household tasks than boys. The difficult time that teenagers are facing during lockdown is mirrored by their parents, who also reported lower levels of wellbeing than parents of younger kids.

Staying connected matters for the wellbeing of children and teenagers.

Parents are often concerned that too much time online negatively impacts their children, who they fear may waste time on social media or become victims of cyber bullying. However, using the internet appears to benefit teenagers during the lockdown. Even after controlling for household wealth, children and teens with internet have higher wellbeing than their unplugged peers.

Children with fewer siblings appear to fare better when sheltering in place.

On average, families with fewer children are likely to report higher levels of wellbeing—and this holds true after controlling for household wealth. Several mechanisms may be at play. Single children are already are used to being flexible and creative, which could lead them to finding social isolation less challenging. Big families may have more limited physical space for each individual child. Finally, children with many siblings may be receiving less attention from parents who divide their time among more children.

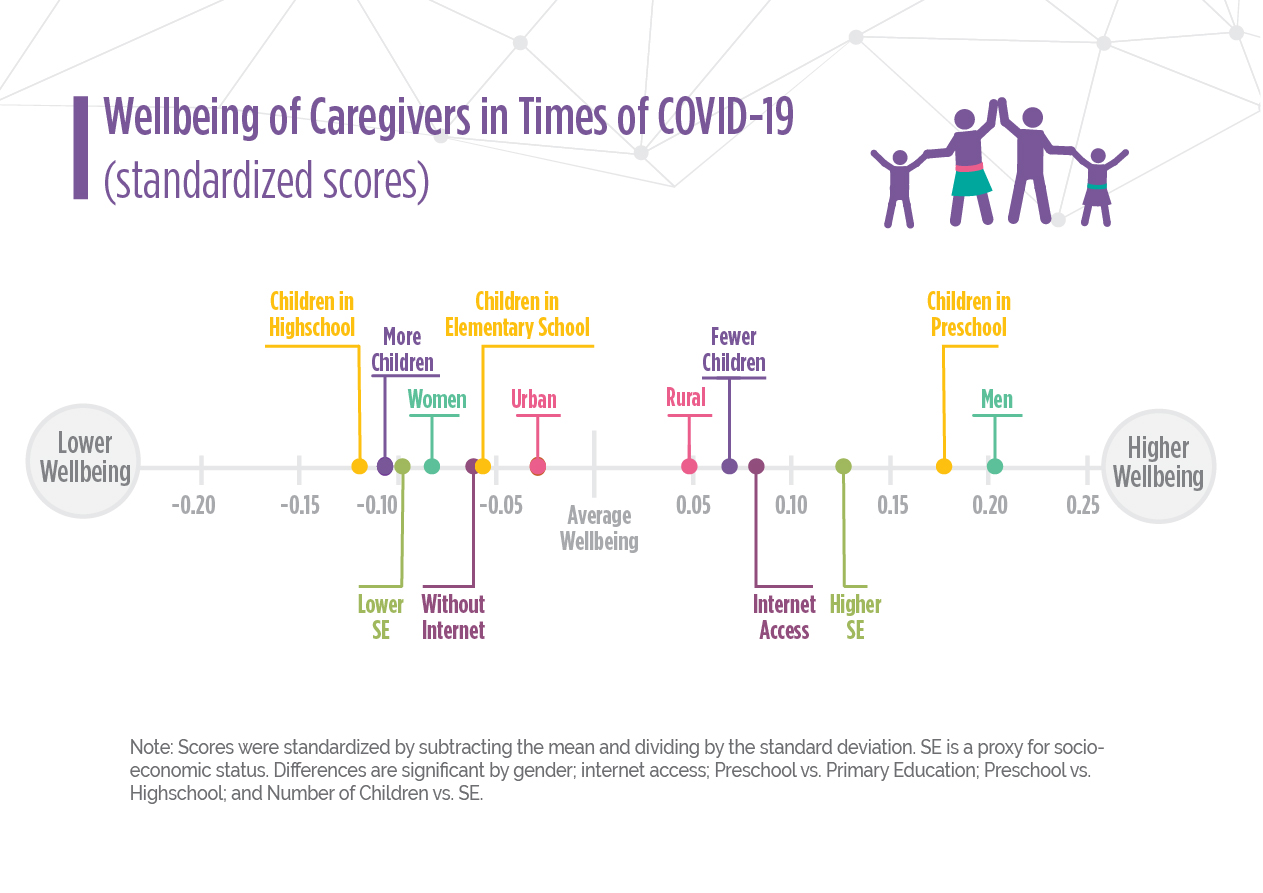

Parenting in quarantine is stressful.

Sheltering in place is not only stressful for children. A large group of parents in our sample report feeling sad and fearful (79 percent). These feelings are understandable, given that many parents have suddenly found themselves juggling the triple role of parent, income provider, and teacher. As is the case for children, larger families are more stressful for parents. The higher the number of children under their care, the lower parents’ reported level of wellbeing. Mothers have particularly low levels of wellbeing, which could be a reflection of them taking on the bulk of the at-home distance education support (67 percent) compared with fathers (26 percent). In most families, women are also in charge of the communications with their children’s school (71 percent) compared with men (only 16 percent).

What now?

While parents’ and children’s physical health is usually the highest-priority concern, it is important to quantify, raise awareness, and develop strategies to address the COVID-19 crisis’s mental health challenges. The scale of the situation is unprecedented, and one can only speculate about the long-term mental health effects on children and teenagers. In Latin America, where teachers tend to take on the role of social workers even in the best of times (and often with limited resources or support), education systems face a looming student mental health crisis.

The distance education programs that ministries have launched during the pandemic, such as Aprendo en Casa, often include tools to foster students’ intrapersonal and citizenship skills.

In addition, IPA and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) are partnering with Ministries of Education in Latin America to design and evaluate interventions to tackle not only learning, but also, the mental health consequences of the lockdown. In the following months we will be testing a large-scale text message campaign to provide parents with pedagogical and self-care support in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Colombia and Peru. In addition, in El Salvador we are working with the Ministry of Education and the IDB to adapt a parenting intervention that was meant to deliver in person to a distance delivery strategy. The intervention will also address the development of parenting skills with a focus on socio-emotional development and wellbeing.

We are curious what you think: What else should education systems do to help students and teachers cope with the mental effects of the pandemic?

1 Parents were asked about their own and their children wellbeing. To measure children’s reported wellbeing, we used an adaptation of the Children Behavior Checklist instrument (CBCL). For adults, we used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-R).